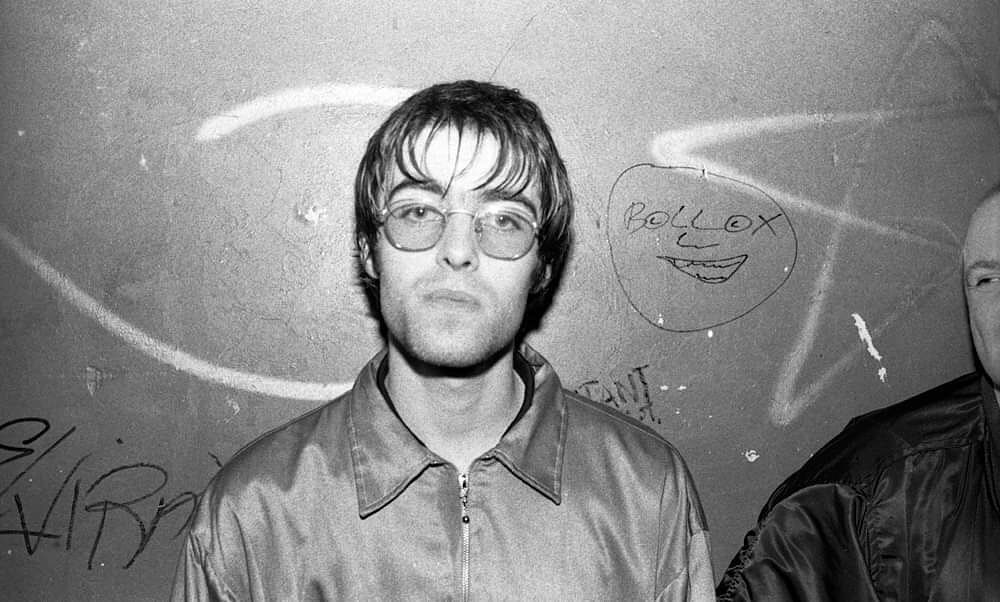

Liam Gallagher is playing drums on my head. I hear a few rhythmic taps, like he’s keeping time on the snare. There’s an occasional swish across the top of the bald napper, casual and cool, Ringo-style. This is happening by the doors of the Astoria on London’s Charing Cross Road and a few music fans are watching, bemused. As they might be. They’ve just been to a feverish gig by the band Ash, but here’s Liam, the most significant face in popular music just now, on the beat with a music journalist.

Liam Gallagher is playing drums on my head. I hear a few rhythmic taps, like he’s keeping time on the snare. There’s an occasional swish across the top of the bald napper, casual and cool, Ringo-style. This is happening by the doors of the Astoria on London’s Charing Cross Road and a few music fans are watching, bemused. As they might be. They’ve just been to a feverish gig by the band Ash, but here’s Liam, the most significant face in popular music just now, on the beat with a music journalist.

I’m thinking of a comedy precedent. When I was a child I would watch Benny Hill on the television, taking the rise out of his sidekick, Jackie Wright. The percussive head taps that Benny served out to Jackie were speeded up on film to humorous effect and because of it, the little Belfast entertainer was forever famous. So, this moment on the evening of August 18, 1995, is my own piece of minor acclaim.

Liam is zipped-up in a designer remake of the M-65 field jacket that American soldiers wore in Vietnam. The singer is 23, unmarked by combat in Burnage, south Manchester, and he may never be so handsome again. His lashes curl magnificently and those eyes are unusually blue. The face is also the scene of divilment and distain, so I’m not sure where this moment will go. But hey, he’s singing for my personal benefit, keeping time on my head.

“He lives in a ’owse…”

(Tappa-Tish, ta-tish-tish, tish)

“A very big ’ouse…”

(Tappa-tappa-tish, tish, ta-tish)

“In ver cuhnt-treeee…”

(Ta-tap, ta-tish, tappa, tappa…tap.)

Well, blow me out, the frontman of Oasis is singing a Blur song. He sings it well, but the delivery is also loaded with contempt. Most of this is aimed at Blur singer Damon Albarn and his working-class malarkey. There’s a bit of extra abuse saved over for myself, in my role of Assistant Editor of the NME. Indeed, the whole performance is Liam’s contribution to a national spectator sport. Two days from now, on August 20, the UK singles chart will be revealed. The top position with be either ‘Country House’ by Blur, or ‘Roll with It’ by Oasis. There has been a great spike in UK record sales, a willingness to join whatever party this is fixing up to be.

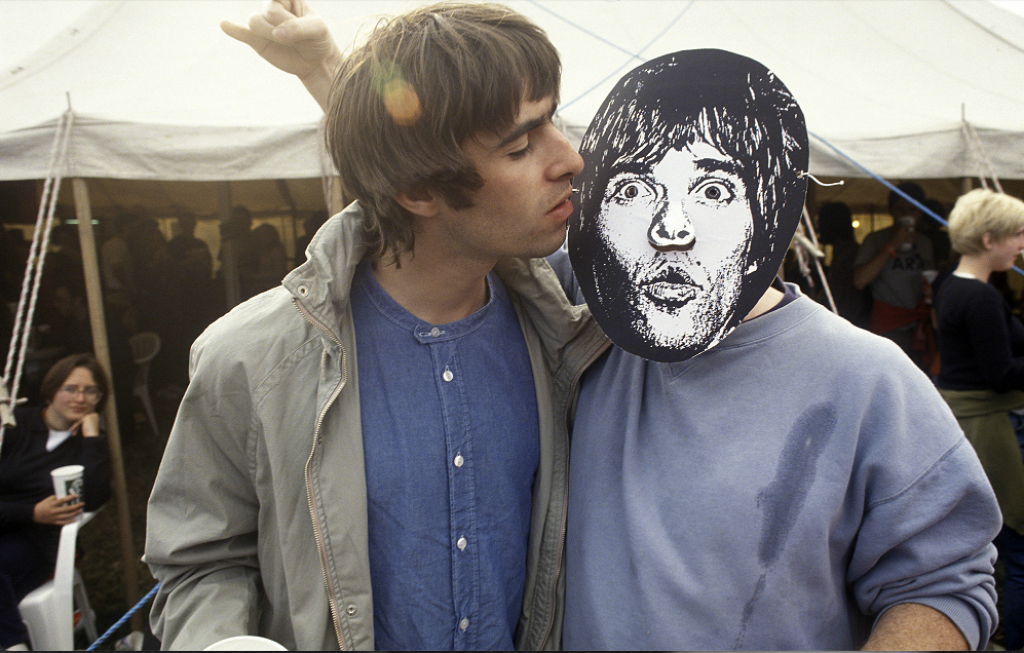

Liam Gallagher & Stu Bailie (half a head away). The Venue, New Cross, 13.05.94. Photo: Martyn Goodacre.

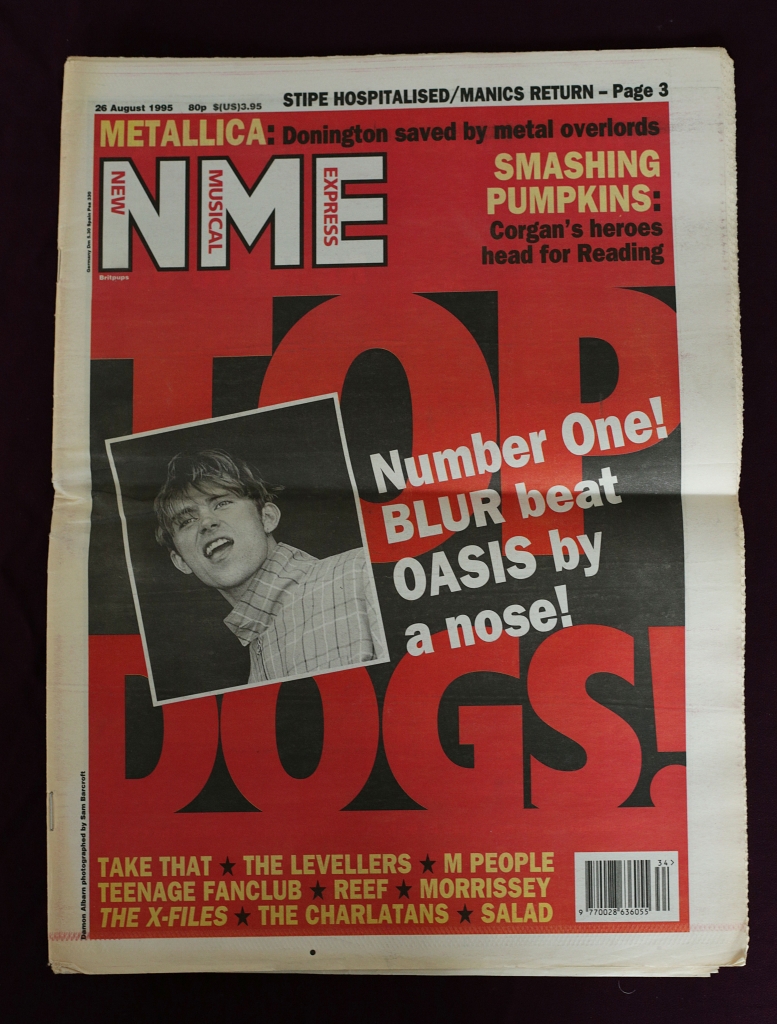

Back at the NME office on the 25th floor of King’s Reach Tower, there are two front covers, ready for the Sunday result and then a Monday trip to the printers. It’s like the scene in Citizen Kane when the Inquirer newspaper has prepared alternate headlines for their election report – either ‘KANE ELECTED’ or ‘FRAUD AT POLLS’. In this 1995 version of the drama, the call is tight. Still, the music industry has been following the midweek sales results and it seems like we know the winning act. We’re leaning towards the artwork that reads like a greyhound race announcement: ‘TOP DOGS! NUMBER ONE! BLUR BEAT OASIS BY A NOSE’.

Meantime, the NME singles reviews page has also given ‘Country House’ the edge. Liam is affronted. “What’s all this bullshit about Single of the Week?” he demands, playing a final paradiddle on my head and then wheeling off into the balmy Soho air with his pal, Bonehead.

Meantime, the NME singles reviews page has also given ‘Country House’ the edge. Liam is affronted. “What’s all this bullshit about Single of the Week?” he demands, playing a final paradiddle on my head and then wheeling off into the balmy Soho air with his pal, Bonehead.

I’m not sure if the singer has conceded defeat with his performance in the Astoria foyer of a Friday evening. He’s certainly showing a lighter touch than brother Noel, who has been lashing out in the press, unhappy with this concocted battle, fighting dirty, saying unwise things that he may regret afterwards.

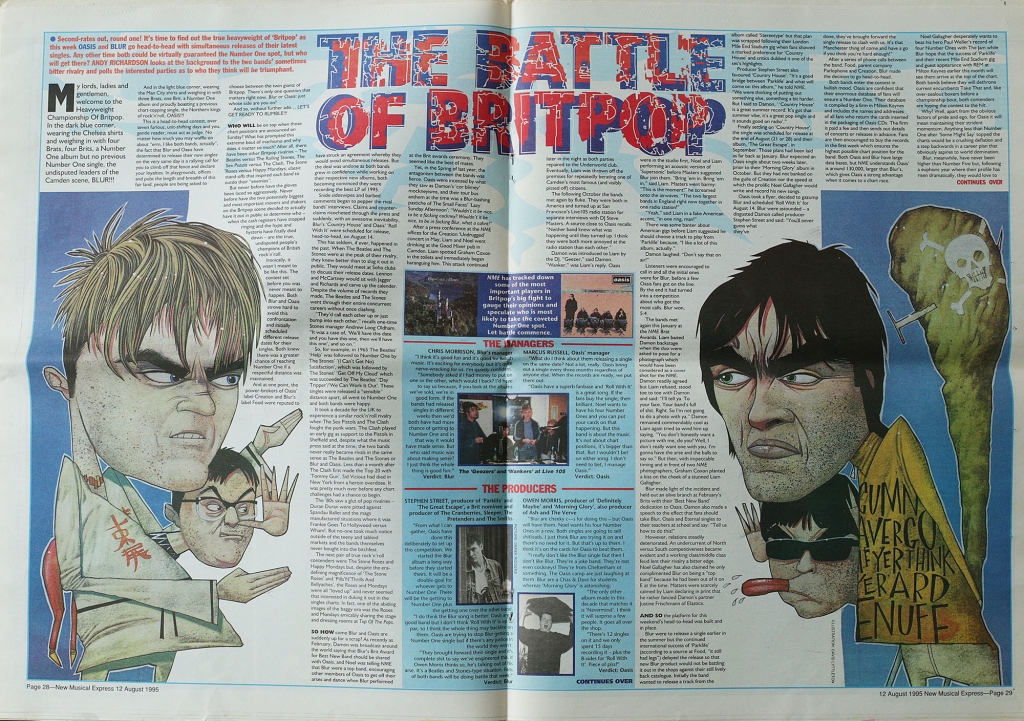

There’s a perfect geometry to the Blur versus Oasis contest. It’s about the entitled south, disabused by ruffians from the north. We see a culture clash of Anglos and Celts, strategy against raw sentiment. Even the two record labels have opposing styles. Oasis are represented by Creation records and Alan McGee – messy, instinctive and often visionary, with a roster of My Bloody Valentine, Primal Scream, Ride, Super Furry Animals and Teenage Fanclub. Meantime, Blur belong to Food Records – arch, knowing and rather pleased with themselves. In turn, the two labels are financed by Sony Music and EMI, so the assault lines are deep.

Back in July 20, I had travelled from London to Bath to see Heavy Stereo, the next hopefuls on Creation Records. The band played a decent show at the Moles club and singer Gem Archer had a deal of sass about him. What really impacted though, was the conversation on the train rides, there and back. The animated Creation people in the carriage were obsessed with the upcoming singles clash with Blur. The fighting talk was endless.

I brought this story into the next editorial meeting at the NME. Other writers had similar ideas about the face-off, including the devious Blur manoeuvres, bringing their single release forward by a week to sharpen the contest. We all agreed that we should signpost the event, rather than let it just happen. These Tuesday meetings at the paper were normally lashed with argument, wit and brawling politics. It was one of the NME’s greatest practices. A half-interesting idea was developed by the team into a compelling read. And thus, Blur versus Oasis was war-gamed by a score of exceptional minds into this bold account.

Andy Richardson from the news desk pulled the story parts together, charting the band enmity through music awards nights, interviews and radio show banter. I added a few stories from an evening with Oasis, The Boo Radleys and Ride on May 5, 1994. We had organised an event with NME readers to promote the upcoming Creation Undrugged night at the Albert Hall, celebrating the label’s ten-year adventure. All had gone well, although the Gallaghers had argued noisily about Primal Scream. The younger brother hated Bobby Gillespie’s choice of footwear. “He wears fuckin’ winklepickers!” Our Kid sneered.

Andy Richardson from the news desk pulled the story parts together, charting the band enmity through music awards nights, interviews and radio show banter. I added a few stories from an evening with Oasis, The Boo Radleys and Ride on May 5, 1994. We had organised an event with NME readers to promote the upcoming Creation Undrugged night at the Albert Hall, celebrating the label’s ten-year adventure. All had gone well, although the Gallaghers had argued noisily about Primal Scream. The younger brother hated Bobby Gillespie’s choice of footwear. “He wears fuckin’ winklepickers!” Our Kid sneered.

After, we headed for Camden and drinks at The Good Mixer on Inverness Street. Graham Coxon from Blur was at the urinals when Liam spotted him and gave out abuse before the chap had even buttoned up his pants. We convened to a gig at The Underworld nearby where Liam continued to attack Graham and was eventually chucked out. I had a pleasant chat outside with Noel, about family in Mayo and the wearing of the Claddagh. I listened to the brothers sing a song, loosely based on the Small Faces and ‘Lazy Sunday Afternoon’.

“Wouldn’t it be nice

To be a facking Cockernee?

Wouldn’t it be nice

To be in facking Blur?

‘Eee’s a cahnt!”

It wasn’t their best lyric, but I liked it.

The NME coverage for the singles battle also profiled the opposing music producers, the band managers and even their radio pluggers. Various artists were polled for the opinions. Justine Frischmann was in it for Blur, while Dodgy abstained. Phil Hartnoll from Orbital didn’t care for the rivalry. “The Beatles and The Stones avoided competition by sorting out release dates,” he reckoned. “I think there should be a bit more of that.” Tim Wheeler from Ash shared a record producer (Owen Morris) with Oasis, so he already had a bias. “Fuck Blur,” said the guitarist, days before he opened his ‘A’ level results live on Radio 1.

The NME coverage for the singles battle also profiled the opposing music producers, the band managers and even their radio pluggers. Various artists were polled for the opinions. Justine Frischmann was in it for Blur, while Dodgy abstained. Phil Hartnoll from Orbital didn’t care for the rivalry. “The Beatles and The Stones avoided competition by sorting out release dates,” he reckoned. “I think there should be a bit more of that.” Tim Wheeler from Ash shared a record producer (Owen Morris) with Oasis, so he already had a bias. “Fuck Blur,” said the guitarist, days before he opened his ‘A’ level results live on Radio 1.

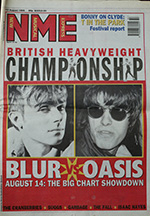

Marc Pechart, the NME art editor, visualised the contest, mocked up as a boxing poster. There it was: ‘THE BRITISH HEAVYWEIGHT CHAMPIONSHIP’. The inside headline was the one that called it in essential terms: ‘THE BATTLE OF BRITPOP’.

We smiled and congratulated each other when the issue arrived from the printers on Tuesday, August 8. Word came back that the bands hated it. Ah, well. Next day, there were two television crews in the office, intrigued by the story. A dozen more followed. By Thursday, it had been a lead story on the national evening news, all over Radio 1 and a starter for much tabloid nonsense. The Times wrote a leader comment. The Financial Times pondered the industry aspects and The Daily Mail was mad for Blur, voice of the home counties. Julie Burchill had her say, sniffy about boys with guitars. The upshot was that everyone with a worthwhile pulse had to declare themselves a fan of either band.

Liam and Stu, King Monkey manqué, Glastonbury 1995.

I had chatted to Liam backstage at Glastonbury a few weeks before the Astoria encounter. I’d been walking around the festival site in an Ian Brown mask, mocking the no-show of the Stone Roses for an NME feature. It was havoc around the Oasis entourage. Robbie Williams was on the lam from Take That, severely confused with bleached blonde hair and a blacked-out tooth. He was ready and willing to get a dismissal from his boy band career and had rocked up to Worthy Farm with two cases of champagne. Robbie wanted to misbehave with his new mates, but the pace was brutal.

There was another casualty nearby. Evan Dando from The Lemonheads had missed his festival slot entirely and wasn’t managing well. So he decided to play acoustic guitar there and then, crooning to a few admirers in the hospitality field. After five minutes he realised that this wasn’t actual recompense for being absent from duty.

There was another casualty nearby. Evan Dando from The Lemonheads had missed his festival slot entirely and wasn’t managing well. So he decided to play acoustic guitar there and then, crooning to a few admirers in the hospitality field. After five minutes he realised that this wasn’t actual recompense for being absent from duty.

In frustration and shame, Evan threw his pint of beer in the air. Everyone watched. The cardboard cup travelled ten feet upwards and dropped on the head of Iain Robertson, Oasis tour manager and veteran of the Parachute Regiment. A direct hit. Instantly, the casual banter stopped. Robbie was alarmed. Liam and Noel assumed stony expressions. I tilted up my Ian Brown mask for a better view.

Iain was a few years out of the army. One of his jobs was to keep order around a band that was wired and causing shenanigans. This he managed well – although he would leave the job a few months later during a dismal Oasis trip to Paris that also prompted a walkout from bassist Guigsy.

The tour manager was vulnerable about the onset of male pattern baldness. His remaining fronds of hair had been groomed and coaxed to hide the evidence. When Evan’s pint had tipped down, the disguise was washed away and the head became a sorry mush. Then Dando came over with a hanky and tried to mop up the beer shampoo, dabbing at the crown. It was hilarious, but we didn’t dare laugh. The singer was led away. Iain eventually uncoiled and showtime was approaching.

Oasis were prepping to play ‘Supersonic’ when a punter chucked a load of eggs at the stage. They resumed the show, now edgy, sometimes outstanding. Noel was in a black duffel coat, bringing ‘Don’t Look Back in Anger’ to unschooled ears. On ‘Live Forever’ Liam stretched out his arms like Cristo Redentor, promising ascension at the Pyramid Stage. Arguably not their greatest show, but an occasion to value. Those early songs were all about yearning, broken biscuits, Irish mother Peggy and the outsider blues. That lost feeling was already starting to dissipate.

Saturday night at Glastonbury was ready for Pulp, filling in for The Stone Roses. The latter were now flaky and accident-prone. Jarvis, though, was adorable. The unpredictable arc of public affection had gifted him this. He took all the generosity and amplified it. The singer reminded us that it wasn’t enough to be a tourist, that you should invest the time with heart, care and consolation. Jarvis wagged those fingers with a practiced elegance. Fifteen years to figure it out: “You can’t buy feelings and you can’t buy anything worth having.” Thus, ‘Common People’ was the greatest win of the season.

Summer 1995 was unusually warm and London was giddy on the fumes. There was beer, ‘beak’ and shouting, wrapped in vintage sports casual. Supergrass had released ‘Alright’, their barrelhouse hit in July and even the older people insisted that they were young and they ran green. Chris Evans was on the Radio 1 breakfast slot, playlisting Black Grape and Edwyn Collins, bellowing at the early risers like he was just returning from a bender. Most likely, he was.

Summer 1995 was unusually warm and London was giddy on the fumes. There was beer, ‘beak’ and shouting, wrapped in vintage sports casual. Supergrass had released ‘Alright’, their barrelhouse hit in July and even the older people insisted that they were young and they ran green. Chris Evans was on the Radio 1 breakfast slot, playlisting Black Grape and Edwyn Collins, bellowing at the early risers like he was just returning from a bender. Most likely, he was.

It was a handy time for the press because people were eager for music. We had an intake of fresh ears, plus artists who could literally provoke news stories by walking to the corner shop. Britpop rescued weathered acts like Pulp, Cast and Paul Weller. New bands were chancing it on the virtue of a haircut or a roaring pub encounter. NME writers were hauling up at King’s Reach Tower with stories about Justine and Sonya, Brett and Alex. It was a crush to fit it on the pages, alongside other music content, which freelance champions still argued for. Because that was our remit, right?

It was easy enough to be a newspaper of record, and it was second nature to cheer on the excellent stuff. But what about the critique? What was actually real about The Real People? It was hard to muster such a conversation with all the front and kerfuffle.

By 1996, the joy was out of it. I watched Oasis at Knebworth Park, like a quarter of a million others. The delusion was spectacular. I stayed around for the John Squire guitar solo on ‘Champagne Supernova’ and every note was a declaration of vacancy.

I wanted to go home. Soon after, I booked a place on the ferry for Stranraer, and we shipped out for Belfast. For me, the Britpop war was over.

(Postscript)

I was returned to the fray in 2002. Oasis played the Odyssey Arena, Belfast, June 30, part of the Heathen Chemistry tour. I thought I might do a review for old time’s sake. So I was down in the pit with a digital camera, writing notes and taking pictures.

I was returned to the fray in 2002. Oasis played the Odyssey Arena, Belfast, June 30, part of the Heathen Chemistry tour. I thought I might do a review for old time’s sake. So I was down in the pit with a digital camera, writing notes and taking pictures.

It was a different Oasis, with added grooming products. Andy from Ride was up there and so was Gem, gainfully employed after Heavy Stereo had gone quiet. Mostly, I watched Noel, who was not exactly at ease. A couple of songs in, and he took the mic and gestured down at the pit.

“See that guy down there taking photos?” he said. “He’s the wanker from NME who started Blur versus Oasis.”

Eh?

“That’s Stuart Bailie”

Liam noticed the drama on stage left and bounded over. He recognised his old percussion partner from 1995. He pretended to unzip his trousers and piss on my head. Then he emptied a bottle of water in my direction.

I was being booed by 9,000 Oasis fans and bullied by the Gallagher brothers. Very strange.

“Take your camera,” Noel said, “and fuck off.”

So I took my camera. And I fucked off.

Stuart Bailie

(From an upcoming anthology of music stories by Stuart Bailie. Details, TBA)

Twitter

Twitter