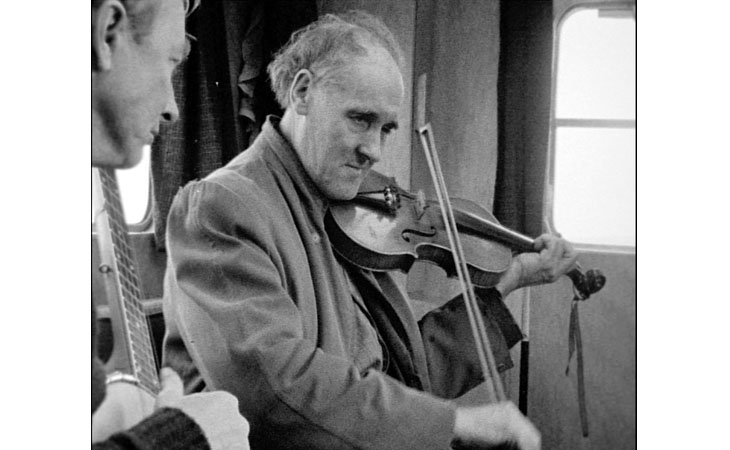

Shallogan, May 1964 and the American songwriter and archivist Pete Seeger is in a caravan during a rainstorm. Fortunately, he is in the company of John Doherty, an iterant fiddle player from south west Donegal. The latter was born in nearby Ardara in 1900 and while he has rarely travelled far from the Bluestack Mountains, his reputation has gone further.

Shallogan, May 1964 and the American songwriter and archivist Pete Seeger is in a caravan during a rainstorm. Fortunately, he is in the company of John Doherty, an iterant fiddle player from south west Donegal. The latter was born in nearby Ardara in 1900 and while he has rarely travelled far from the Bluestack Mountains, his reputation has gone further.

Seeger is joined by his wife Toshi, who films the encounter. Dr. Malachy McCloskey, a patron and supporter, is helping to manage the conversation and the musical flow. Peter Kennedy, the English collector is recording the audio and pushing for content.

But John Doherty won’t be hurried or coerced. Sometimes his songs are abridged and teasing. His answers can be wry and quietly mocking. Music has been part of the family business for generations, back to Hugh Doherty and his wife Nannie Rua MacSweeney at the break of the nineteenth century, to piping tunes of the seventeenth century and the Flight of the Earls, when the Gaelic order suffered a great change. He’s not about to give all his gold away for a few visitors.

John’s repertoire includes airs, jigs, reels, waltzes, mazurkas and more. The highland pipes were part of the family lineage and so this informs his playing. But he has also learnt from shipwrecked sailors and travelling shows. He tells amazing stories about how the music was gifted by the fairies and spooked by the banshees. There is theatre when his strings recreate the sound of a fox hunt with the horses stamping, the beagles in pursuit and the brutal conclusion. He will often talk about altercations at the crossroads. He’s a showman and a shaman.

Doherty is the keeper of a strain of music that had flourished in the 1850s and had sustained long after in this isolated area. In time, 78rpm records from Michael Coleman had come in from America, the Sligo fiddle style gone international. This became the dominant style but some had resisted. John had been inspired by recordings from the Scottish player James Scott Skinner and this had enhanced his outlook. During his old wanderings from Ballybofey to Carrick and the Croaghgorm moorlands, he was a welcome figure and since many of the households kept a fiddle, he didn’t need to travel with one. It was considered an honour to provide hospitality for the man and John would also get by from fixing and selling household utensils and creating milk jugs and sundry containers from sheets of tin.

Pete Seeger’s Irish visit has involved meetings with the McPeakes in Belfast and the Makems in Armagh. He’s plainly delighted by the Doherty meeting and sometimes he accompanies the man on the five string banjo. But this is emphatically John’s gig. It seems that he’s emerged from a period of family mourning and may not have played for six months. He needs to trim his fingernails before he can start. Occasionally he seems stressed and forgetful and the cuffs on his big coat are frayed. But there’s also a poise about the artist. Like the Griots of West Africa, he has been born into the role.

“My father used to tell the story about the night I was born. The woman was careless and put me down on top of the tallboy. And what do you think but that I picked up the bow and was holding it between my finger and my thumb. ‘O Maggie, do you see this?’ he says, ‘He’ll handle it better than anything else’.”

He plays ‘The Blackbird’ as an air and then as a hornpipe. ‘Easter Snow’ is a beautiful paradox and there’s the story of the woman who set off those feelings. John plays in a maverick style with a dropped wrist. To reach the high notes he has to maneouvre his hand at speed, but this is achieved with seeming grace.

This is the period of the ballad boom, a reaction to the success of the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem in New York. Irish music has adapted and so many of the bars are full of báinín jumpers and stomping choruses. But Seeger has found what he was seeking in that rickety caravan, an opening into something more ancient.

Scratchy snippets of the 1964 encounter have been in circulation for some time, as evidenced here and here. But in 2012 a chance discovery at the Library of Congress revealed a lot more of the Toshi Seeger archive with Doherty. In time, this was matched to a cache of Peter Kennedy audio. It’s not a perfect match and there are moments when the camera or the recorder fail us. But the parts that are in synch are significant, precious.

I get to witness this wonderful recreation upstairs at the Imperial Bar in Bangor during the Ulster Fleadh. Danny Diamond and Conor Cardwell are fiddle players and academics and they have been integral to this work. They talk us through the peculiarities of this archive and the resonant context of John Doherty. It changes how we approach his music. What other documentation there is of the musician mostly dates to the Seventies, when he was presented as the old fella with the cap and the modest manners. But the encounter in 1964 is more lyrical and strange. John’s demeanor is that of a younger figure, nobody’s fool, possessed by music and ancestry, a bit magical.

Stuart Bailie

Twitter

Twitter