Eamon Melaugh, a civil rights activist and social campaigner from Derry, died 8 December 2025, aged 92 He was a formative figure in the city’s resistance culture, which began in earnest after 1959 when he returned home from a stint in Scotland. He became a core member of the Derry Housing Action Committee (DHAC) and the Derry Unemployment Action Committee (DUAC), precursors to the civil rights movement.

Eamon Melaugh, a civil rights activist and social campaigner from Derry, died 8 December 2025, aged 92 He was a formative figure in the city’s resistance culture, which began in earnest after 1959 when he returned home from a stint in Scotland. He became a core member of the Derry Housing Action Committee (DHAC) and the Derry Unemployment Action Committee (DUAC), precursors to the civil rights movement.

His method was non-violent resistance. Along with Eamonn McCann and aided by Fionnbarra Ó Dochartaigh, he organised the first Civil Rights march in Derry, October 5, 1968. This was violently repressed by the Royal Ulster Constabulary. Eamon’s nurturing instincts led himself and his wife Mary to raise 11 children and then foster an additional 15. He was also moved by the plight of street children in India and set up a charity, Action With Effect, that raised £900.000 for social justice projects. A collection of his documentary photography, Derry: The Troubled Years, was published in 2005.

Some of the most iconic images of Eamon date back to his time as a broadcaster on the pirate station, Radio Free Derry in 1969. The station went live in January 10, following on from the fractious People’s Democracy March from Belfast to Derry. They returned to the air in August during the Battle of the Bogside. Eamon was pictured in the Daily Mail in his hat and welder’s goggles. The disguise was in vain since the newspaper reporter then named him in the story. He also featured in a Granada TV documentary at the time.

Some of the most iconic images of Eamon date back to his time as a broadcaster on the pirate station, Radio Free Derry in 1969. The station went live in January 10, following on from the fractious People’s Democracy March from Belfast to Derry. They returned to the air in August during the Battle of the Bogside. Eamon was pictured in the Daily Mail in his hat and welder’s goggles. The disguise was in vain since the newspaper reporter then named him in the story. He also featured in a Granada TV documentary at the time.

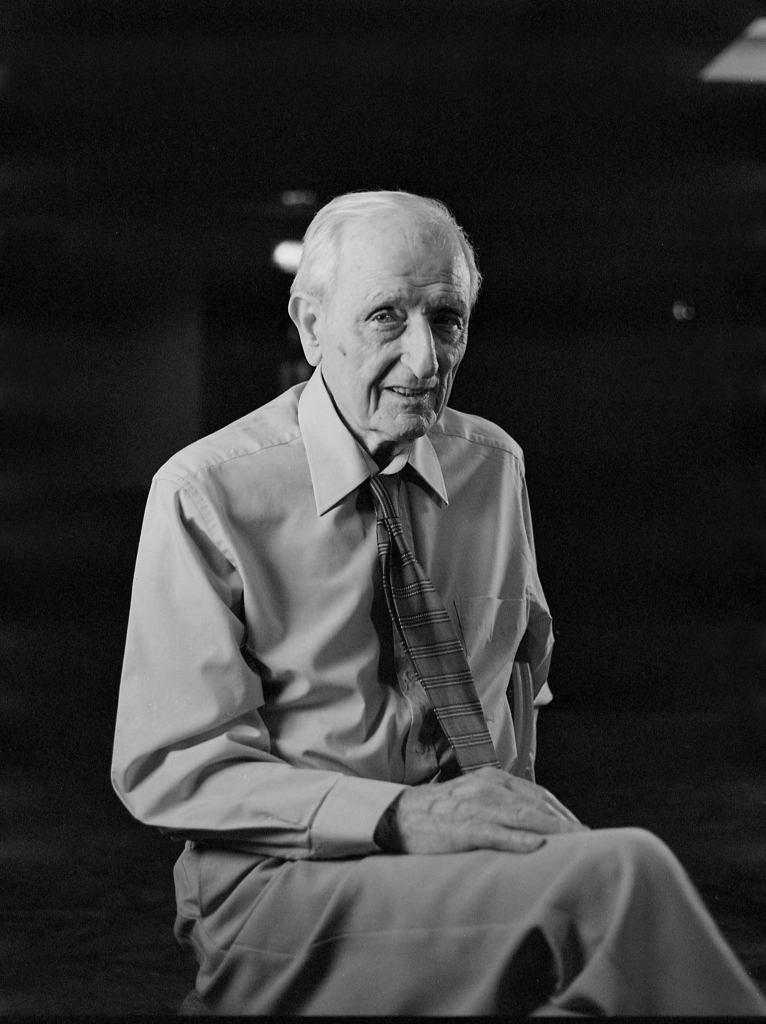

Eamon Melaugh, Derry, 22 January 2019. Photography by Stuart Bailie

I interviewed Eamon in his hometown in 2019. This was part of an unfinished project with the late film maker Vinny Cunningham. I was keen to hear about his part in the radio station and he was generous with his stories. Firstly, I wanted to know about the broadcasting hardware in 1969, which was apparently installed by Jim Sharkey, father of Feargal.

“It was a metal box and it had a couple of dials on it. It was crude, but it was good. It served a function. it was a voice of an individual who was part of the people, being myself and Eamonn McCann. We were the only two that broadcast, he did the first one and then he gave it up. I did about six or seven, but no more than that. [Tommy McDermott, Ross O’Kane and others also contributed].

“The antiquated device was presented to Eamonn McCann and it came from somebody in the People’s Democracy. Basically, we didn’t have electric and so I got this old hand-cranked record player and one of the things I decided to do was play music. I was on this thing for hours. I mean, I had my photograph taken with the goggles. The guy wrote in his piece in the Daily Mail – [he said] I made a half hour unscripted broadcast. I was on the fecking thing for about six hours, you know.

“You needed an aerial about 150 feet long. I had it on the top of the high flats [Rossville] and I had to throw the cable out of the window and it almost touched the ground before we could broadcast. I’m in a concrete bunker at the top and this is going on for hours. I’m giving a running commentary on what was happening and I was looking at four concrete walls but I had two people doing runners and coming and telling me. This was at The Battle of the Bogside.

“Two other guys came in all excited, they had picked up this radio message that the city engineer had offered the security forces to turn off the water to the Bogside. I retaliated immediately by saying, well, if you turn off the water to the Bogside, we’ll turn off the gas to the whole of Derry. The Gas Yard was in the Bogside.”

Eamon, presenting Radio Free Derry, August 1969

Eamon was keen to playlist the music of Paul Robeson, the American singer who had become a voice for the black civil rights movement.

“Paul Robeson would have been a great hero of mine. I’m into classical music, but this man was defiled by the American institutions of politics. He was a remarkable man. Politically, he was far ahead of his time. He stood up for what he considered to be his rights. He was an important person in my life.”

The station’s reach was the Creggan, the Bogside and the Brandywell – 888 acres and 25,000 people. But the message went further, as Eamon explained.

“Well I’ll tell you a story. It was heard in Detroit and the story told to me, I was on the air and this guy from Detroit phoned his sister in Derry and I was on, and she held the phone to the radio and I was heard in Detroit.”

So Radio Free Derry was music, conversation and interviews?

“I would have tried to get my socialist philosophy out to the wider public and I used it honestly as an instrument of peace. See, a lot of people think of me as a violent individual. I was violently opposed to what was going on, but I never was violent about it. I opposed violence. I wasted a lot of time trying to talk to people [about violence]. I believe that when I have to meet my maker, I will have to answer not only for everything I’ve done, but for every thought I’ve thought, and those who die having spilt innocent blood… I mean in the days when a wee woman kissed her RUC husband going out to duty in the morning and somebody coming back several hours later to say that he is dead. Blown to pieces, I felt for that woman. Violence is never the answer. Dialogue – the ability which we all have to give.”

Radio Free Derry started in the Creggan and moved to the Rossville Flats. Did it move several times?

“Well, it moved around because the army were searching for it. I mean, I broadcasted twice from my kitchen in Circular Road, and they actually got the radio one night in Carrickreagh Gardens, the army got it. What happened was, it was in a family called Browns, they were a family of four and they’re all dead now, but the army were carrying out a whole lot of searches that evening and seemingly they had two and a half minutes to each house. A soldier looked under the bed and he called to his commanding officer ‘we’ve got Radio Free Derry! ’And your man said, ‘leave it there – our two and a half minutes are up.’ And they left.”

Eamon also talked to me about the importance of the American civil rights anthem, ‘We Shall Overcome’

“Look, it mightn’t have been our song, but it was our message. It was a statement of a risen people – we are equal to the rest of them. ‘We Shall Overcome’ was a dramatic statement made by people who were saying to the authorities, we have had enough – no longer are we prepared to tolerate second class citizenship. And by the singing of it, it was a wonderful way to express that. It was eloquent. The proposition that there’s a problem there- ‘We Shall Overcome’’and that theme was taken up. It was sang every day on the streets of Derry. Almost every day.”

Eamon Melaugh, and Eamonn McCann, Derry, 5 October 2018. The 50th anniversary of the first Civil Rights march in Derry. Photography by Stuart Bailie

Also, the founding aims of the Civil Rights Movement were that it should be non-sectarian and non-denominational. Nobody was to be excluded…

“It was extremely important. I tried my living best to keep politics out of the Civil Rights struggle. I canvassed in the Fountain and Wapping Lane for people to come out on the 5th of October [1968]. I actually canvassed, and the conditions in Wapping Lane were every bit as bad as any other street in Derry. I tried to keep politics out of it. It was a struggle for elemental civil rights and struggle, shouldered by the people themselves and the tactic of getting them, to keep them. You couldn’t stop them as well, it was a brilliant tactic, it [music] pacified them, they marched and they expressed their contempt for the system by singing. There was no stones involved. There was no guns involved and there were no petrol bombs at that time.

“Music had a great influence at the time. If you got people singing ‘We Shall Overcome’ and ‘We Shall Not Be Moved’, you can’t do that and throw petrol bombs at the one time. So it had a calming influence, no question in my mind about that. No question.”

Eamon Melaugh, 1933-2025.

Stuart Bailie

Twitter

Twitter